The next topic we covered is Remediation. Remediation is a media theory focused on the incorporation or representation of one medium in another medium. When talking about remediation I think it is important to establish some important terms and their meanings:

Remediation – The process by which new media technologies improve upon or remedy prior technologies. The formal logic by which new media refashions prior media forms.

Hypermedia – Computer applications that present multiple media (text, graphics, animation, video) using hypertextual organisation. For instance, games and websites. Operates under the logic of Hypermediacy.

Immediacy – A style of visual representation whose goal is to make the viewer forget the presence of the medium and believe that they are in the presence of the object of representation. One of two strategies of remediation; the other is hypermediacy.

Hypermediacy – a style of representation whose goal is to remind the viewer of the medium.

Hypertext – A method of organisation and presenting text on the computer. Textual units are presented to the reader in an order that is determined, at least in part by electronic links that the reader chooses to follow. Hypertext is the remediation of the printed book.

Skeuomorph – A derivative object that retains ornamental design cues from structures that were inherent to the original.

According to the book “Remediation: Understanding New Media” by Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin (2000), remediation is one of the defining characteristics of new digital media as digital media is constantly remediating its predecessors. Remediation theory states that the media’s existence is related to other media forms; it is fundamentally comparative and assumes that media does not possess autonomous formal or technical specificity, but that it exists only in relation to other media forms and practices. The theory also argues that new media does not remove or replace old forms of media, but rather it defines their newness through the refashioning of the present media forms.

Butler and Grusin believe that we are currently in a period so rich in technology that new technology is being produced faster than our culture, education and legal systems can keep up and that our culture has an inherent contradictory imperative for immediacy and hypermediacy, which they call the double logic of remediation. They state that:

“Our culture wants to both multiply its media and to erase all traces of mediation; ideally, it wants to erase its media in the very act of multiplying them” (2000: 4-5). People want to be immersed in the media, and they don’t want that immersion to be broken; because of this technology continually needs to evolve and progress in an attempt to become invisible.

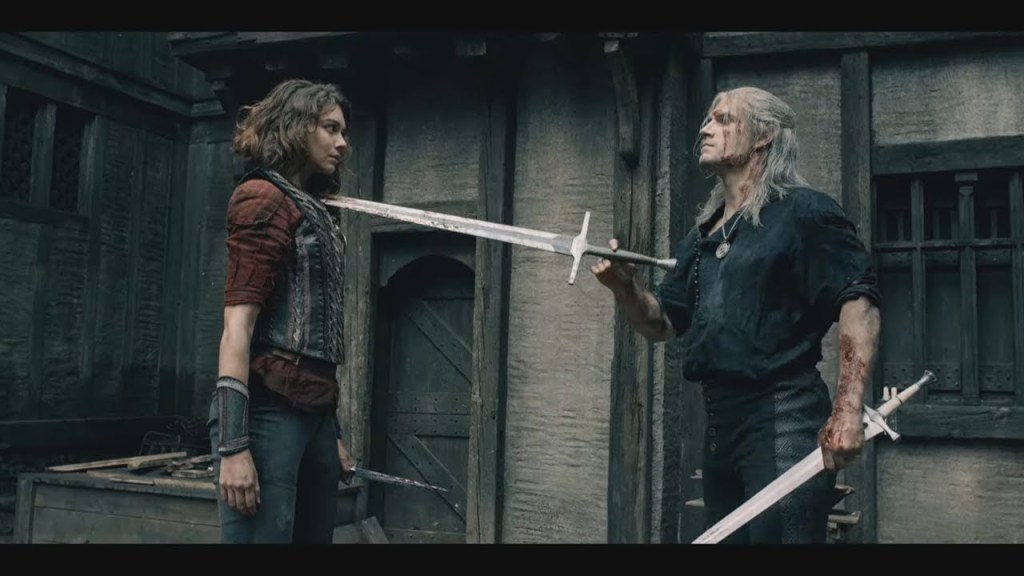

Butler and Grusin believe that we have an “insatiable desire for immediacy” (2000: 5); that we are obsessed with live point-of-view experiences, with the feeling of intimacy with the characters and world and feeling like a fly-on-the-wall to the events playing out on screen. Filmmakers will spend tens of millions of pounds to film or real-life locations, to recreate period and realistic, believable costumes and places to make the viewer feel as though they were really there. In recent years this trend has transitioned into TV thanks to shows like Game of Thrones (Beniof and Weiss 2011-2019) which shot over a total of 25 locations and whose last season had a budget of $15 million dollars per episode (Pisapia 2019). Netflix’s The Witcher (Schmidt 2019) first season was shot across a total of 21 locations and whose first season, consisting of 8 episodes, had a total budget of around $80 million (Ayala 2020)(Fig 1-3.). Viewers of shows like this want to forget that they are watching a TV show and be transported into the world of the show, because of this the worlds have to be believable otherwise the immersion is broken; this ability to be transported to new worlds is one of the reasons that I enjoy shows like the “Witcher” so much. Butler and Grusin state that the “medium itself should disappear and leave us in the presence of the thing represented” (2000: 6). It is also worth noting that the Witcher is a great example of remediation, and how its many different forms allow the audience to experience the world, characters and story in a different way. Originally a collection of short stories that became a fully fledge book series, the universe has been expanded into video games, comics and not the Netflix TV series (Fig 4-6.).

However, Butler and Grusin say that we cannot be left alone by these old and new media forms, that there is a double logic to remediation. Even when watching something as immersive as high-budget films and TV shows the media used it constantly being made aware to us, in real-life situations you aren’t able to be a fly on a wall or be able to be in one situation while also viewing someone else experience simultaneously. Film and TV also often mix media together, like the use of cinematic scores that are played over the top of the footage to help increase the emotion of the scene. Butler and Grusin believe that the two logics, immediacy, and hypermediacy, however contradictory to each other, not only “coexist in digital media today but are mutually dependent” (2000: 6). They state that:

“Immediacy depends on hypermediacy. In the effort to create a seamless moving image, filmmakers combine live-action footage with computer composition and two- and three-dimensional computer graphics … Even the most hypermediated production strives for their own brand of immediacy. Directors of music videos reply on multiple media and elaborate editing to create an immediate and apparently spontaneous style, they take great pain to achieve the sense of ‘liveness’ that characterise rock music” (2000: 6-9).

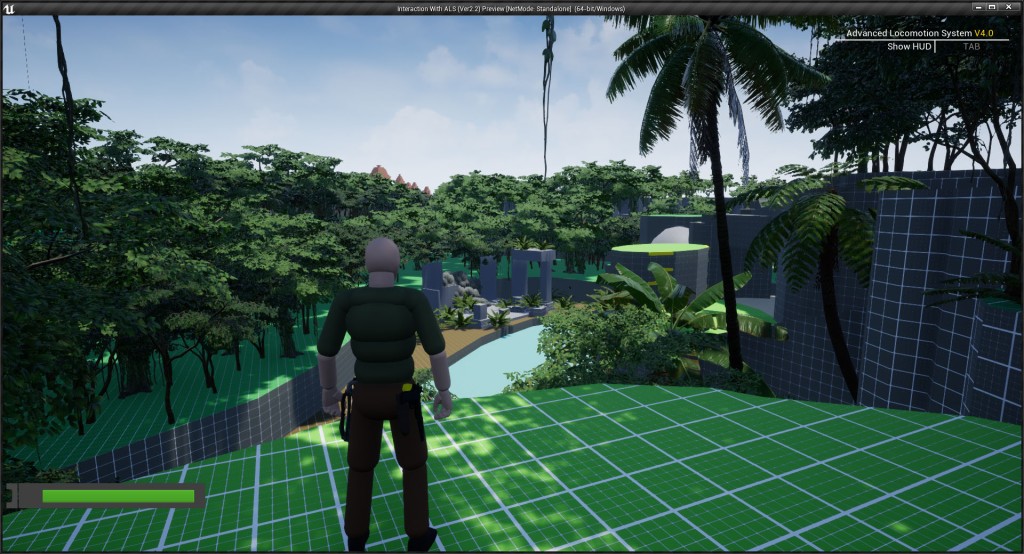

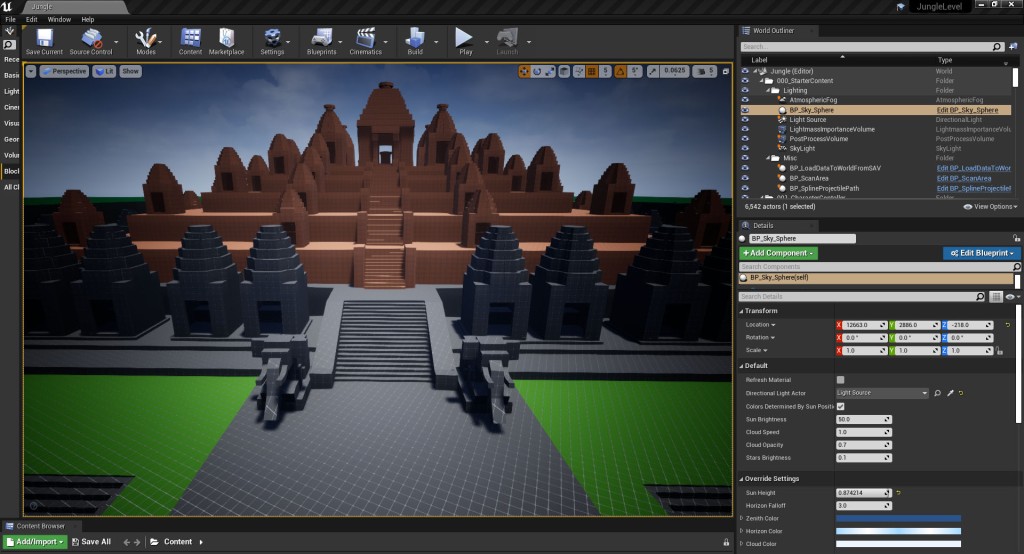

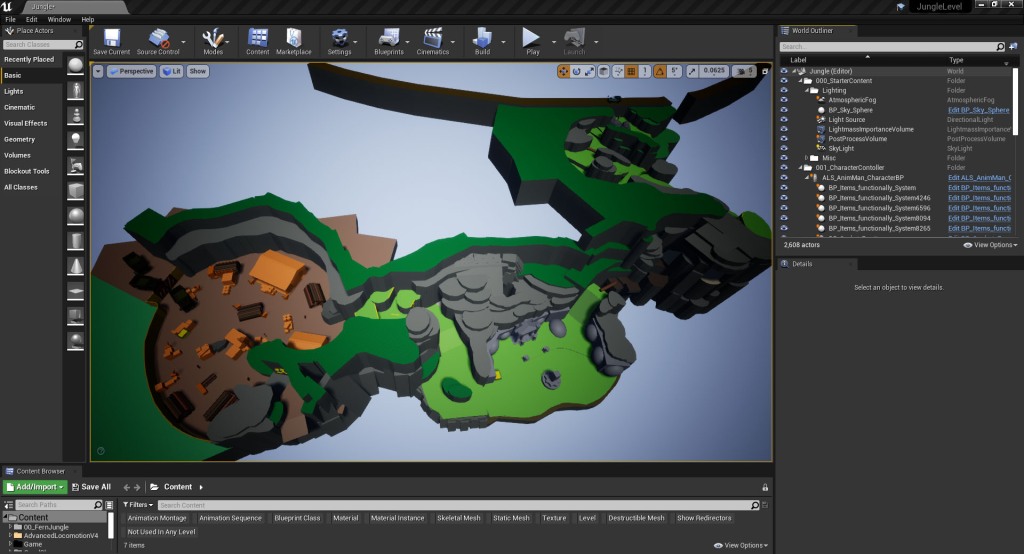

I believe that video games are a perfect example of the double logic of remediation. Video games strive to be immersive; they want you to forget that you are playing a game and to become fully immersed in the world, and the story you are playing. But the medium itself constantly reminds the player that they are playing the game, the controls, the UI, and even the world itself remind the player of the technology that is being used. Games are fully explorable worlds, that are often densely populated with NPC’s; the issue with this is making sure that they logically exist and could support all the people that live in them. The way that games get around this is by making their worlds believable and “credible” (Jakob Mikkelsen and Eskil Mohl 2019) not necessarily realistic. By approaching games this way; having UI and being able to play as multiple characters in the same world, it no longer removes the player from the experience; instead, they add another layer to them. Video Games are a perfect example of the double logic of remediation; they seek to be seamless in their use of multiple media, to make the player fully immersed in the world they are playing in but they also put the multiple different types of media directly in front for all the players to see.

“Ultimately, all I wanted was for players to feel like they were in the real world. I wanted them to be able to apply real-world common sense to the problems confronting them, and I thought recreating real-world locations would encourage that kind of thinking.”

Warren Spector

References:

AYALA, Nicolas. 2020. “The Witcher’s Bidget: How Much The Netflix Show Cost to Make.” Screenrant [online]. Available at: https://screenrant.com/witcher-tv-netflix-budget-cost-game-thrones-comparison/ [Accessed 25 September 2021]

BOLTER, Jay David. and Richard. GRUSIN. 2000. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, Mass: MIT.

MIKKELSEN. Jakob and MOHL. Eskil. 2019. Hitman 2’s Jakob Mikkelsen and Eskil Mohl by GMTK Dev Interviews [YouTube user-generated content]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pBApJdzKnPA

PISAPIA, Tyler. 2019. “Breaking Down Game Of Thrones’ $90 Million Final Season Budget.” Looper [online]. Available at: https://www.looper.com/155278/breaking-down-game-of-thrones-90-million-final-season-budget/ [Accessed 25 September 2021].

TV Series:

BENIOFF, David and D.B. Weiss. 2011-2019. Game of Thrones. [TV Series]

SCHMIDT, Lauren. 2019. The Witcher. [TV Series]

Figures:

Figure 1: SCHMIDT, Lauren. 2019. The Witcher. [TV Series]

Figure 2: SCHMIDT, Lauren. 2019. The Witcher. [TV Series]

Figure 3: SCHMIDT, Lauren. 2019. The Witcher. [TV Series]

Figure 4: SAPKOWSKI, Andrzej. 2009. Bloof of Elves – A Novel of the Witcher. London, United Kingdom: Orbit

Figure 5: SCHMIDT, Lauren. 2019. The Witcher. [TV Series]

Figure 6: The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt. 2015. CD Projekt RED, CD Projekt RED.

Leave a comment