At the beginning of last semester, in GAM701 we were shown the experimental animation by Heider and Simmel from 1944 which shows how humans easily anthropomorphize and apply meaning to even simple shapes. This animation (fig. 1.) was created by Heider and Simmel as part of their experimental study into apparent behaviour and is a landmark study in the field of interpersonal perception, in particular, our attribution process when making judgments of others (Heider and Simmel 1944).

Of the thirty-four subjects in the study thirty-two described the shapes as people while the other two described them as birds. There were also some common themes found throughout the interpretations of the test subjects. Nearly every subject described the interaction between the two triangles as a fight and that the bigger triangle was locked in the house. When describing the interaction between the big triangle and the circle nearly all thirty-four test subjects describe the circle as being chased by the big triangle. When looking at the movement of the shapes almost all the subjects described the shapes as controlling the interactions, both between the shapes themselves and the movement of the door; the shapes move the door, the door isn’t moving the shapes (Heider and Simmel 1944). The Heider Simmel experiment shows that humans are capable of taking simple shapes and applying deeper meaning to them, but why do we do this? Humans as a species don’t like ambiguity; we like to fill in the blanks, make connections and see patterns in order to make sense of our world. This tendency, of making connections in order to understand the world around us, is called apophenia, a term coined by the German Neurologist Klaus Conrad (reference) and means:

“The tendency to perceive a connection or meaningful pattern between unrelated or random things, such as objects or ideas”

(Merriam-Webster Dictionary n.d.)

It is often commonly associated with pareidolia which is:

“The human ability to see shapes or make pictures out of randomness”

(Merriam-Webster Dictionary n.d.)

As humans we naturally look for patterns, it is one of the ways that as a species we evolved and survived as it allows us to understand what we are seeing around us and the world as a whole, something that Michael Shermer calls “patternicity” (2008). Shermer argues that humans have naturally evolved to be “pattern-recognition machines that connect the dots and create meaning out of the patterns that we think we see in nature” (2008). Our natural ability to look for patterns can also be applied to stories. When Journey (2012) was realised 9 years ago it was widely regarded as a masterpiece, both in the art style and the narrative that is told with a “grace and subtlety rarely employed in video games” (Clements 2012). Donlan’s review of the game for Eurogamer praised the game for its narrative describing how the “storyline left careful gaps so as to allow for a handful of different interpretations” (2012). The reason for the success of Journey ambiguous story is that humans love to attribute meaning to the unclear. While not everyone enjoys ambiguous or abstract narratives, IGN’s review of Hyper Light Drifter (2016) by Brandin Tyrrel listed the abstract nature of the story as a negative, something that fans of the games strongly disagreed with (fig. 2. and 3.); it is a popular way to tell a story as it allows players to use their own knowledge and experiences in relation to the game resulting in unique and personal stories for the players (Gaynor 2013).

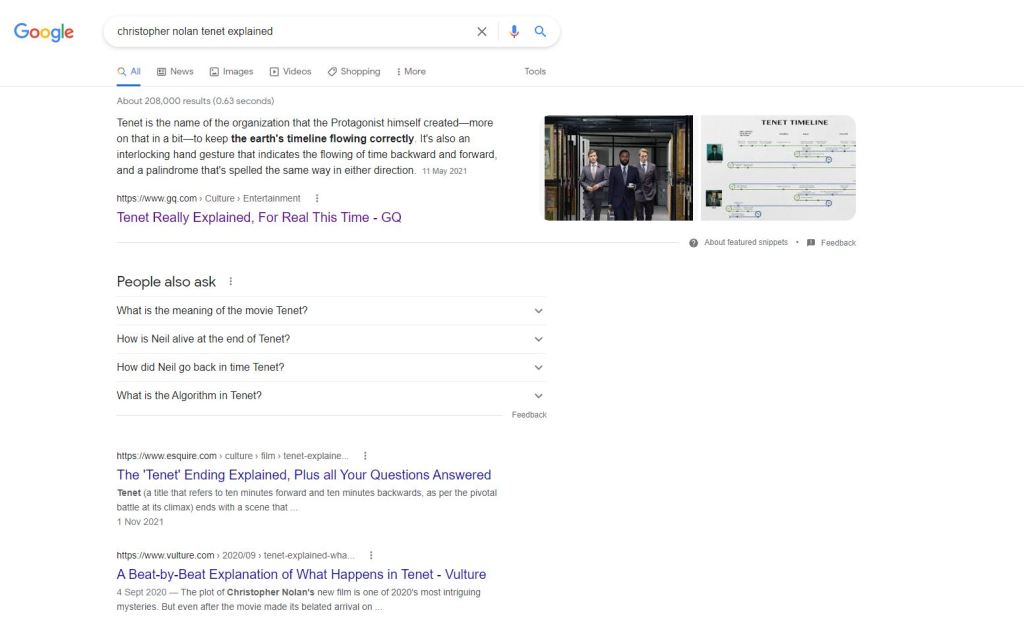

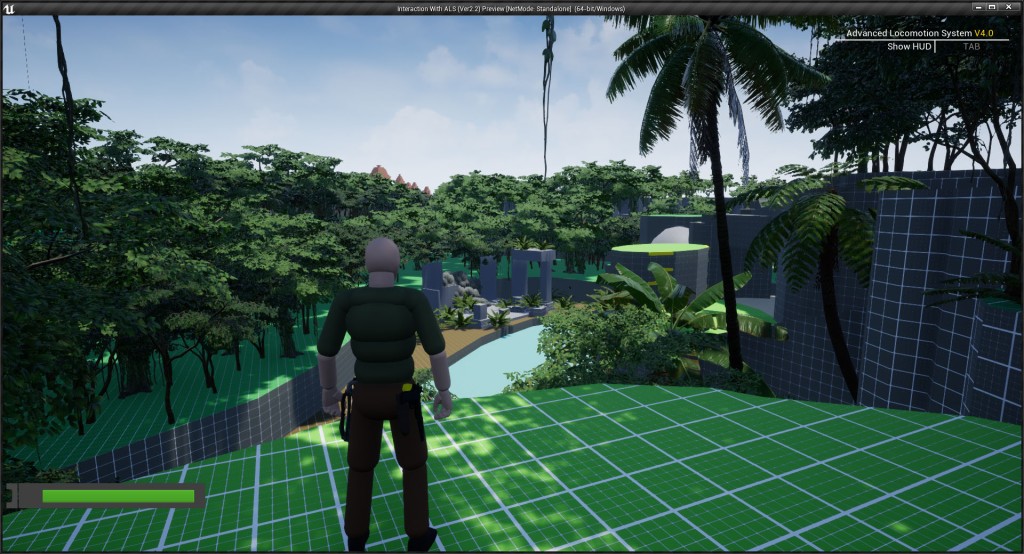

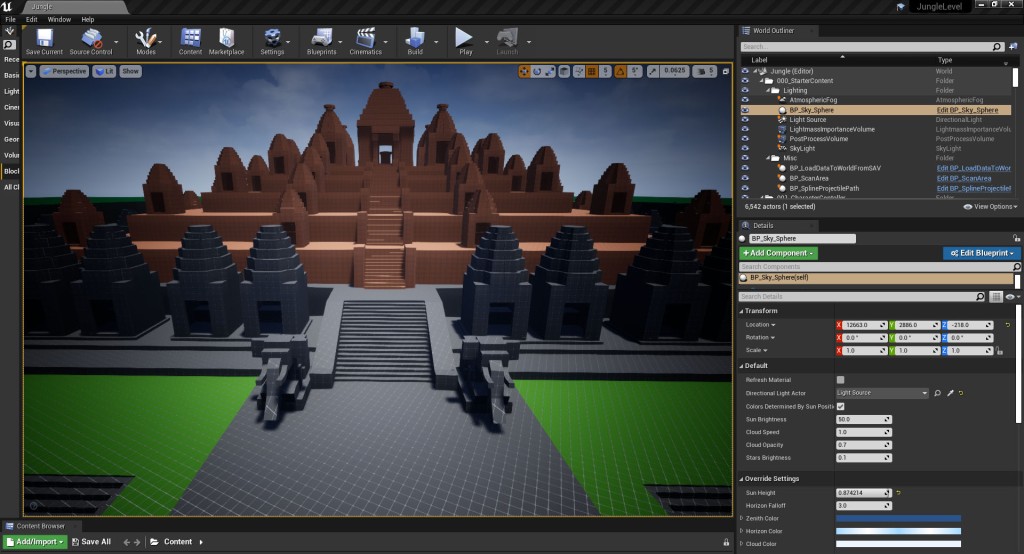

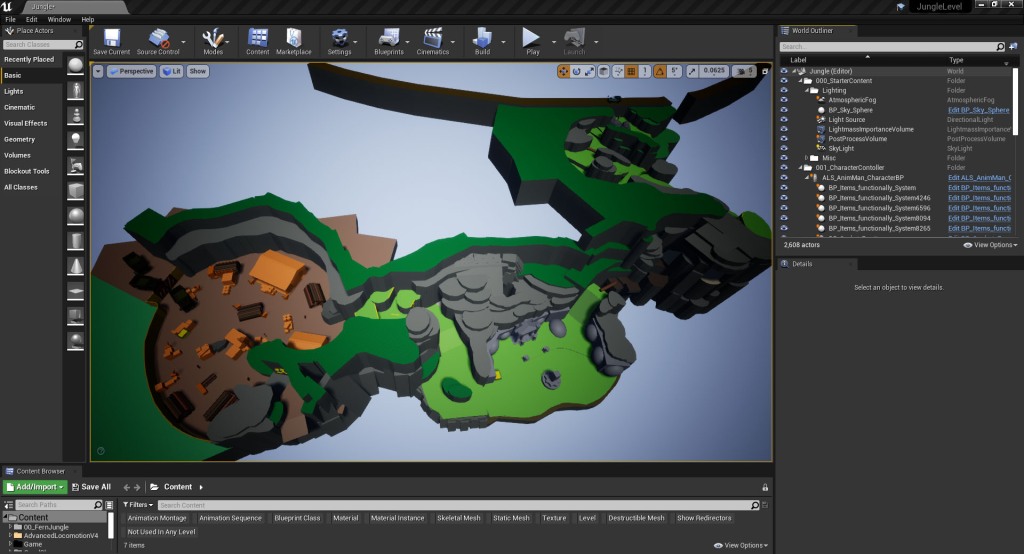

Allowing an audience to interpret a narrative rather than outright telling them the story is used in films as well as games. Whenever a new Christopher Nolan film is released they are soon followed by many ending explained videos and articles, the most recent example of this being Tenet (2020) (fig. 4. and 5.).

Stories, and in the case games, that allow the player to interpret their own meaning are so compelling because they invite the player to write their own story and apply their own meanings. Games as a medium place the player in the role of the main character, players are active participants in the narrative in contrast to movies where you are just a viewer. Games with sparse details invite the player to use their own experiences to create their own interpretation of the story, increasing engagement and as a result investment. Being able to work out the meaning of an abstract narrative for a game also provides the player with a feeling of achievement and joy which in turn release dopamine in the brain. There is strong evidence to suggest that dopamine increases our ability to notice patterns as we get joy from being able to work something out (Krummenacher et al. 2009). This release of dopamine isn’t just applicable to games with abstract stories but to any game that features puzzles for the player to solve or environmental storytelling, players enjoy being able to work out where a story is heading or how to solve a puzzle which increases their investment is a story.

“To me, games have an extremely great and still unrealized potential to influence man. I want to bring joy and excitement to people’s lives in my games, while at the same time communicating aspects of this journey of life, we are all going through. Games have a larger potential for this than linear movies or any other form of media.”

Philip Price (1997)

References:

DONLAN, Christian. 2012. “Journey Review: Just deserts?” Eurogamer [online]. Available at: https://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2012-03-01-journey-review [Accessed 27th January 2022]

CLEMENTS, Ryan. 2012. “Journey Review: We walk until this path is done” IGN [online]. Available at: https://www.ign.com/articles/2012/03/01/journey-review [Accessed 27th January 2022]

GAYNOR, Steve. 2013. “AAA Level Design in a Day Bootcamp: Techniques for In-Level Storytelling.” GDC Vault [Video Online]. Available at: https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1017639/AAA-Level-Design-in-a [Accessed 27th January 2022]

HEIDER, Fritz, and Marianne SIMMEL. “An Experimental Study of Apparent Behavior.” The American Journal of Psychology, vol. 57, no. 2, University of Illinois Press, 1944, pp. 243–59. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/1416950.

KRUMMENACHER, Peter. Christine, MOHR. Helene, HAKER. and Peter BRUGGER. 2009. “Dopamine, Paranormal Belief, and the Detection of Meaningful Stimuli.” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(8), 1670-81.

MERRIAM-WEBSTER DICTIONARY. n.d. “Apophenia” Merriam-Webster [online]. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/apophenia %5BAccessed 27th January 2022]

MERRIAM-WEBSTER DICTIONARY. n.d. “Pareidolia” Merriam-Webster [online]. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/pareidolia [Accessed 27th January 2022]

PRICE, Philips. 1997. Interviewed by James Hague in Halcyon Days [online]. Available at: https://dadgum.com/halcyon/BOOK/PRICE.HTM [Accessed 27th January 2022].

TYRREL, Brandin. 2016. “Hyper Light Drifter Review: A cryptic laser show with sword and speed.” IGN [online]. Available at: https://www.ign.com/articles/2016/04/14/hyper-light-drifter-review [Accessed 27th January 2022]

SHERMER, Michael. 2008. “Patternicity: Finding Meaningful Patterns in Meaningless Noise” Scientific American [online]. Available at:https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/patternicity-finding-meaningful-patterns/ [Accessed 27th January 2022]

Games:

Journey. 2012. Thatgamecompany, Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Hyper Light Drifter. 2019. Heart Machine, Heart Machine

Films:

NOLAN, Christopher. 2020. Tenet [Film].

Figures:

Figure 1: An Experimental Study of Apparent Behavior. 1944. Heider, Fritz, and Marianne Simmel.

Figure 2: Hyper Light Drifter Review by IGN. 2019

Figure 3: YouTube comment section for IGN’s review of Hyper Light Drifter. 2019.

Figure 4: YouTube search for Christopher Nolan’s Tenet (2020) explained

Figure 5: Google search for Christopher Nolan’s Tenet (2020) explained

Leave a comment