What are ‘Serious Games’? In a 2007 Microsoft Research talk, Ian Bogost describes ‘Serious Games’ in the following way:

“There can be more to video games than mindless entertainment, and the ‘Serious Game’ movement argues that video games are not only a mirror to our culture but create ways to play with and manipulate important social and political questions” (2007).

But what are ‘Serious Games’? When talking about ‘Serious Games’ there are several definitions that are often used. The first formal definition of ‘Serious Games’ came from Abt who presented games as a way to improve education (1970). The examples he provided were mainly around pen-and-paper based games, as the video game industry was still in its infancy. Jansiewicz built on this idea of ‘Serious Games’ as an educational tool, publishing a book describing games as a tool in aiding teaching and listing a game he invented to teach the basics of US politics as an example (1973).

It wasn’t until 2002 that the definition of ‘Serious Games’ was updated by Swayer who redefined the term to mean the use of video game technology to convey a serious purpose or topic beyond pure entertainment (Swayer 2002). Sawyer went on to help shape the ‘Serious Games’ industry through the Serious Game Initiative and conferences like the Serious Game Summit and Games For Health (Sawyer, 2009). Swayer’s definition of ‘Serious Game’ is shared by many people and influence the definitions created later on; such as Chen & Michael definition, that ‘Serious Games’ are “Games that do not have entertainment, enjoyment or fun as their primary purpose” (2005). However, what falls under the domain boundaries of the Serious Games are still subject to debate. Corti (2007) explains that the “Serious Game” industry brings together participants from a wide range of fields, such as Education, Defense, Advertising, Politics, etc. who do not always agree on what is and what is not a part of the Serious Games industry. However, a commonality can be found across all professional fields despite the debate of what is and isn’t a serious game; ‘Serious Games’ are ones that use people’s interest in video games to capture their attention for a variety of purposes that are not just pure entertainment.

In their 2005 book, Chen & Michael (2005) classified Serious Games according to markets, forming eight distinct categories:

- Military Games

- Government Games

- Educational Games

- Corporate Games

- Healthcare Games

- Political Games

- Religious Games

- Art Games.

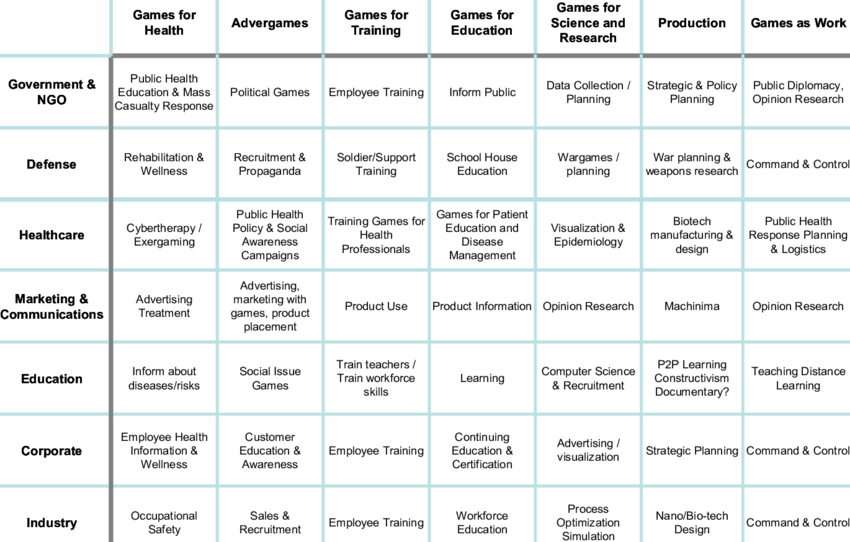

In a paper presented at the Serious Game Summit in 2008 Swayer and Smith put forward a preliminary taxonomy of ‘serious games’ (fig. 1.).

Sawyer and Smith put forward this taxonomy as they believed that “all games are serious” it just depends on how you interpret the content, how you classify the game and the extent of the seriousness (Sawyer and Smith 2008). This is a sentiment shared by Bogost who uses Animal Crossing: Wild World (2005) as an example of a game that has a serious note to it, describing how playing the game with his 5-year-old son led to conversations around consumerism and long-term debt (2007).

Bogost, like Sawyer and Smith, believes that video games have an expressive power that opens a new domain for persuasion; they are a “new form of rhetoric ” (Bogost 2007). This new form of rhetoric is something that Bogost has called “procedural rhetoric” a type of rhetoric that is tied to the core affordances of computers. Not only can games be used as a way to support existing cultural and social beliefs but they can also be used to propose alternatives and disrupt established beliefs; leading to what Bogost describes as potentially significant social changes. While persuasive video games could be used for conveying many types of beliefs Bogost lists “politics, advertising and education” as having the most potential uses.

‘Serious Games’ Examples:

That Dragon, Cancer (2016)

That Dragon, Cancer (2016) (fig. 2., 3., 4. and 5.) is a videogame that serves as a love letter to the developer’s son Joel Green. It is an immersive narrative-driven experience to memorialise Joel and through his story, honour the many he represents. That Dragon, Cancer is a poetic and playful interactive retelling of Joel’s 4-year fight against cancer.

The game uses a mix of first-person and third-person perspectives and utilises point-and-click interactions. It is a two-hour narrative experience that invites the player to slow down and immerse themselves in a deeply personal memoir which features audio taken from home videos, spoken word poetry, and themes of faith, hope, despair, helplessness and love. The game also features in-game tributes to the loved ones of over 200 of the Kickstarter backers.

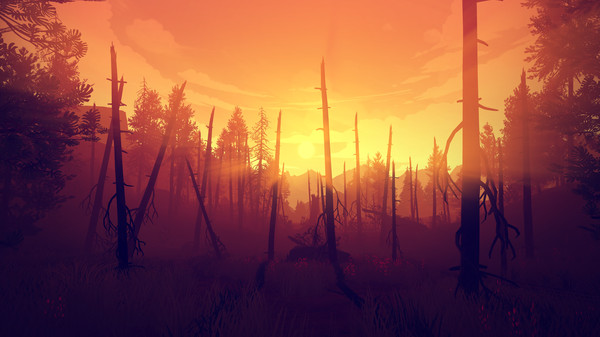

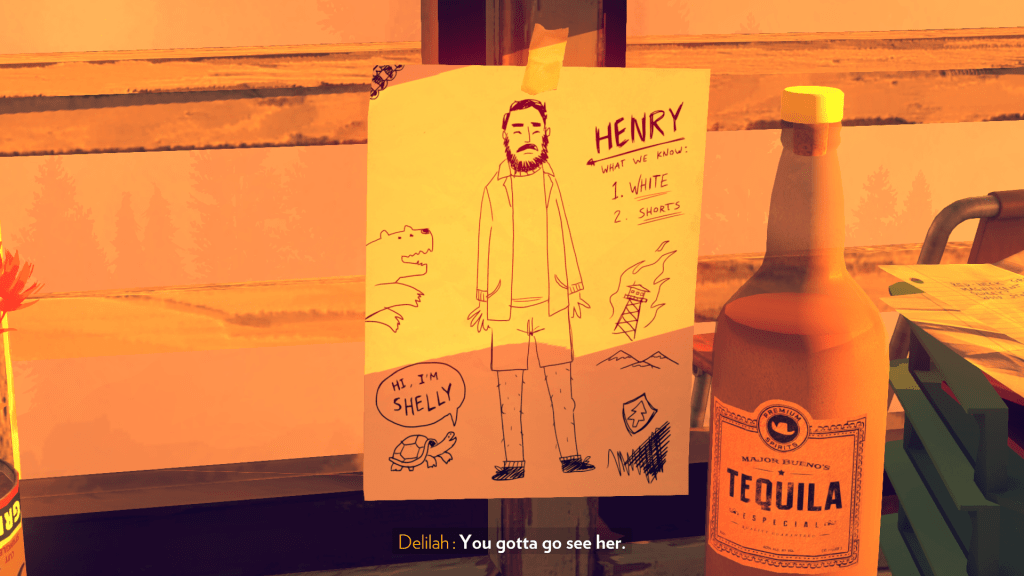

Firewatch

Firewatch (2016) (fig. 6., 7., 8., and 9.) is a first-person walking simulator, narrative adventure game which takes place in the wilderness of Wyoming. You play as Henry, a newly designated fire lookout assigned to an outpost in the area, who’s also trying to flee a troubled past. The game deals with the topics of dementia, loneliness, love and death.

Firewatch (2016) tells the story of Henry’s struggling to come to terms with his wife’s diagnosis of dementia in her late thirties and his unhealthy relationship with alcohol. When Julia’s parents step in to take care of her and take her home to Australia Henry is left alone on the other side of the world. Instead of taking the time to sort himself out and join his wife, he chooses instead to run away from his problems and join the firewatch service at Two Forks Lookout. Through exploration of the surrounding area, you uncover clues about mysterious occurrences in the area. Henry’s only means of communication is a walkie-talkie connecting him to his supervisor, Delilah. Players can choose from a number of dialogue options or choose not to communicate at all, with the player’s choices influencing the tone of Henry’s and Delilah’s relationship.

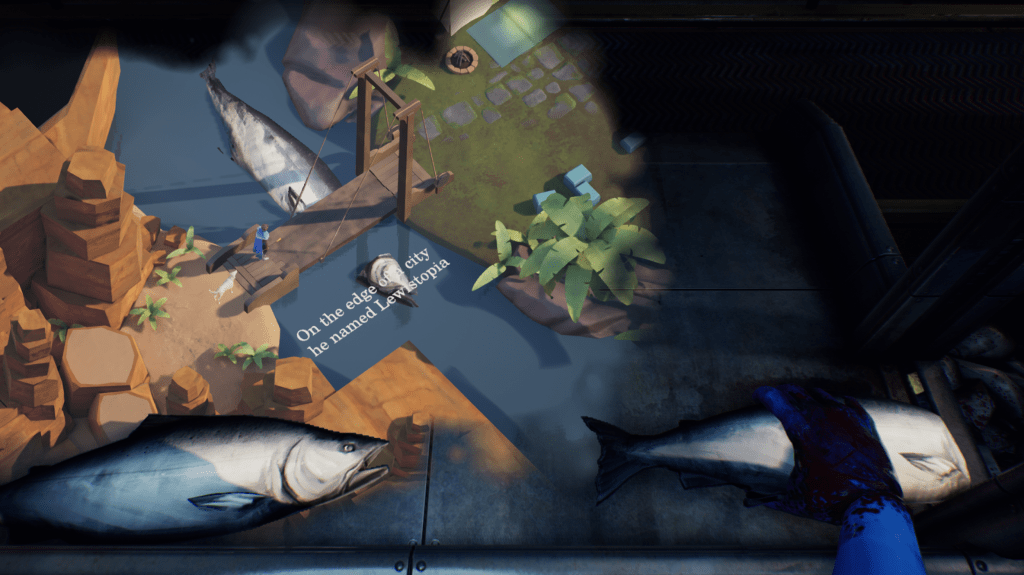

What Remains of Edith Finch

What Remains of Edith Finch (2017) is a collection of strange tales about a family in Washington state. As Edith, you’ll explore the colossal Finch house, searching for stories as she explores her family history and tries to figure out why she’s the last one in her family left alive.

The game centres around a family that don’t understand mental illness. The stories revolve around characters who are dealing with depression, schizophrenia, anxiety, and general feelings of self-doubt and isolation, however as they’re growing up in a family that doesn’t understand those concepts their tragic deaths, which may or may not be suicides, as considered an unavoidable curse placed upon the Finch family.

While no character comes straight out and says, that they’re struggling mentally as this would have taken away from the story being told, it is strongly implied. What Remains of Edith Finch portrays characters struggling with their mental health in a way that feels believable and without reducing them to stereotypes. Each character’s story is told in a unique way that reflects their personality the only constants are that each is played from a first-person perspective and that each story ends with that family member’s death (fig. 10., 11., 12., and 13.).

“Even in dark times, we cannot relinquish the things that make us human.”

Khan – Metro 2033 (2010)

References:

ABT, Clark, C. 1970. Serious Games. USA, Viking Press.

BOGOST, Ian. 2007. “The Persuasive Game: The expressive power of Video Games” Microsoft Research [online video]. Available at: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/video/persuasive-games-the-expressive-power-of-videogames/ [accessed 29 January 2022].

CHEN, Sande. & David, MICHAEL. 2005. Serious Games: Games that Educate, Train and Inform. USA, Thomson

Course Technology.

CORTI, K. 2007. “Serious Games – Are We Really A Community?.” Game Developer [online]. Available at: https://www.gamedeveloper.com/pc/opinion-serious-games—are-we-really-a-community- [accessed 29 January 2022].

JANSIEWICZ, Donald, R. 1973. The New Alexandria simulation: a serious game of state and local politics. USA, Canfield Press.

SAWYER, Ben. 2002. Serious Games: Improving Public Policy through Game-based Learning and Simulation. USA, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

SAWYER, Ben. 2009. Foreword. In RITTERFELD, Ute., Michael. CODY, &. Peter. VORDERER, (Eds.), Serious Games: Mechanisms and Effects. USA, Routledge.

SAWYER, Ben. & Peter, SMITH. 2008. “Serious Game Taxonomy”. Paper presented at the Serious Game Summit, San Francisco, USA.

Games:

Animal Crossing: Wild World. 2005. Nintendo, Nintendo.

That Dragon, Cancer. 2016. Numinous Games, Numinous Games.

Firewatch. 2016. Campo Santo, Panic.

Metro 2033. 2010. 4A Games, Deep Silver.

What Remains of Edith Finch. 2017. Giant Sparrow, Annapurna Interactive.

Figures:

Figure 1: “Serious Game Taxonomy” by SAWYER, Ben. & Peter, SMITH. 2008. Presented at the Serious Game Summit, San Francisco, USA.

Figure 2: Screenshot from That Dragon, Cancer. 2016. Numinous Games, Numinous Games

Figure 3: Screenshot from That Dragon, Cancer. 2016. Numinous Games, Numinous Games

Figure 4: Screenshot from That Dragon, Cancer. 2016. Numinous Games, Numinous Games

Figure 5: Screenshot from That Dragon, Cancer. 2016. Numinous Games, Numinous Games

Figure 6: Screenshot from Firewatch. 2016. Campo Santo, Panic

Figure 7: Screenshot from Firewatch. 2016. Campo Santo, Panic

Figure 8: Screenshot from Firewatch. 2016. Campo Santo, Panic

Figure 9: Screenshot from Firewatch. 2016. Campo Santo, Panic

Figure 10: Screenshot from What Remains of Edith Finch. 2017. Giant Sparrow, Annapurna Interactive

Figure 11: Screenshot from What Remains of Edith Finch. 2017. Giant Sparrow, Annapurna Interactive

Figure 12: Screenshot from What Remains of Edith Finch. 2017. Giant Sparrow, Annapurna Interactive

Figure 13: Screenshot from What Remains of Edith Finch. 2017. Giant Sparrow, Annapurna Interactive

Leave a comment