Many popular games have their roots in mythologies and folklores that are centuries, if not thousands of years old with their supernatural and fantastical setting becoming strong selling points for video games.

From medieval-inspired games such as The Witcher 3 (2015) and Elder Scrolls (2022) series to the Ancient World setting of Assassin’s Creed: Origins (2017) and Assassin’s Creed Odyssey (2018), myths, legends and folklore have been a major source of inspiration for the video gaming industry, especially over the last decade.

Both the heroes and enemies found in games are borrowed and reinterpreted from the myths, legends and folklore of cultures that are hundreds of years old and form the foundation for many game’s settings and stories. Over the last ten years, many of the best-selling and popular series have turned to the tales and religions of Ancient Egypt and Ancient Greece as well as Slavic and Nordic culture and beliefs. The history of ancient cultures and their mythology have become a vital source of inspiration for the video game industry, though these mythologies, legends and folklore are often used in a similar way.

Norse Mythology has become a key element of pop culture in recent years, with shows like The Last Kingdom (2015-2022) and Vikings (2013-2020) drawing heavily on it for inspiration. This trend has also moved into video games, with franchises like Assassins Creed and God of War (2018) using Norse Mythology as the inspiration for their most recent games.

God of War started as a Greek-inspired franchise, but its latest release in 2018 and the upcoming God of War Ragnarok (2022) release are both set in a Norse inspired world. Throughout the first game of the Nordic reboot, the player follows Krator who has settled in Midgard to raise his son, Atreus. Kratos’ hope for peace is prevented when his wife dies and he must face multiple Norse gods on a quest to spread his wife’s ashes at the highest peak in the Nine Realms. Alongside the many Norse Gods that Krator has to face there are also the creatures of myth and folklore. The creatures of Norse Folklore and Mythology featured within the game are for the most part fairly faithful to the original Norse tales with the changes made being minimal to make them more suitable for the game’s world. An example of this are the Draugrs, the most common enemies found throughout the game. In Norse Folklore, Draugr are undead creatures, with the word Draugr meaning “dead inhabitant of a cairn” in Old Norse (Cleasby 1974). Draugr live in their graves, guarding the treasure buried alongside them, with the quality of their afterlife being related to the quality of their burial mound. In God of War (2018), Draugr are specifically undead warriors that died in battle and refused the call of the Valkyries to Valhalla as they were blinded by anger and revenge. As a result, they are doomed to forever roam Midgard in rage as a husk of their previous selves.

God of War (2018) doesn’t just take inspiration from Norse tales for their creatures. Wulvers are a creature from Gaelic and Celtic folklore and where the game’s interpretation of folklore differs from that of the original source material. In the originally Gaelic/Celtic folklore, Wulvers are a wolf-man hybrid originating in the Shetland Islands. They were believed by the ancient Celts to be a symbol of the in-between stage of man and wolf having evolved from wolves and never having been human at all. Folktales of Wulvers tell how they would take pity on the needy; leaving fish on the windowsills of poorer families and helping lost travellers, by guiding them to nearby towns (The Scotsman 2016 and Macqueen 2018). In comparison, Wulver’s are portrayed as ferocious enemies within the games. They are powerful, formidable beasts that resemble werewolves that possess immense strength and speed. When used within the game the creators of God of War (2018) seem to see their physical resemblance to werewolves and as a result stereotyped them as vicious and ferocious enemies for the player to fight. While the idea of a ferocious man-wolf hybrid creature that the player can fight doesn’t feel out of place within the world of God of War (2018) it is interesting that they choose to take a peaceful creature from Celtic/Gaelic mythology and turn it into a ferocious enemy rather than use something like the Berserker, the bear warrior, or Ulfhednar, the wolf warrior (Crawford 2017), from Norse stories.

God of War isn’t the only game that combines Norse and Celtic folklore and mythologies together, the newest Assassin’s Creed, Valhalla (2020) also combine the two mythologies together. The game is set in Britain during the Dark Age which marked the gradual transition from the Pagan Religions of old Europe to modern Christianity, with the Christian Church having gained a firm foothold in Britain. The main Pagan Religions featured in the game are that of the Norse Paganism, Celtic Paganism and the Irish Pagan Druids. Though the game is mostly set in Britain, the majority of folklores featured are of Norse origins due to the player taking on the role of the Viking Eivor; when Celtic folklore is featured it is in the form of monsters that need to be killed. While Assassins Creed: Valhalla (2020) does fall into the trap that most video games do, off using folklore and mythology as inspiration for the enemies that the player fights, the game does explore and use Norse tales on a much deeper level than its predecessors. Whereas most games use the more well known Norse tales of the Gods like Odin, Thor and Loki, Assassins Creed: Valhalla (2020) delves further and uses the lesser-used tales such as that of Ratatoskr the Squirrel AC: Valhalla (2020) whose job was to carry messages up and down the world tree from the Eagle at the very top to the monstrous snake who lived in its roots (Sigurðsson 2020). While Ratatoskr doesn’t play a large role within the game, the player’s interaction with them comes in the form of flyting a mini-game found throughout the world of Valhalla, it does show the developer’s efforts to embed the Norse Folktales and Myths into the world as well as using them as inspiration for the enemies.

While Assassins Creed: Valhalla (2020) does well with the historical accuracy of Ireland in its DLC Wrath of the Druids (2021), with the world featuring Ring Forts that were widely used as circular fortified dwellings in Ireland at the time (Ubisoft North America 2021), the game does fall into the same trap as God of War (2018) with its use of Celtic Mythology. The DLC’s story revolves around a cult of druids called the Children of Danu that the player must defeat in order to maintain the peace and see the unification of Ireland achieved. While Assassins Creed: Valhalla’s interpretation of Druids does make them interesting enemies to fight, it does reduce the Celtic folklore and mythology down to mostly a combat encounter. As Ireland has become mostly occupied by Christianity by the time that the game takes place, the few surviving Pagan sites that the player gets to encounter are mainly through combat with the Children of Danu. These caves and pagan ritual sites that the druids occupy are often submerged in a toxic fog that causes Eivor to hallucinate if the player gets too close; with most of the seven Druid enemy types gaining enhanced powers while in the fog, like Venomous Druids being able to magically teleport around the battlefield and the Fire Druids bursting into flames if you get too close. Though these design choices make sense for the player experience, they provide interesting and engaging combat experiences to the player, it does end up reducing the Celtic folklore to its barbaric side and mostly ignores their role as poets, historians, and judges. Even Ciara, one of the few Druids within the DLC that fulfils the role of Poet and advisor to the High King of Ireland eventually becomes another enemy for the player to have to fight. This isn’t the only time that Celtic folklore and mythology are used in this way within Assassins Creed: Valhalla (2020), during the main storyline of Valhalla the player meets Modron, the high priestess and leader of the druidic cult, the Daughters of Nimue during the Glowecestrescire alliance quests. As with Ciara, Modron starts out as a wise and well-respected character within her community but in an effort to protect her druid beliefs from being wiped out by the spread of christianity ends up becoming a character that the player is forced to fight and potentially choose to kill. Though Celtic Pagan/Druid and Norse Pagan beliefs are very similar and both face the evergrowing threat of christianity, it is interesting that Ubisoft chose to have the two religions mostly in conflict and focused on their more violent aspects.

Another collection of Myths, Legends and Folklore that has become a popular source of inspiration for video games is that of Polish or Slavic Folklore; thanks in part to CD Projekt RED’s Witcher Series (2007-2015). The Witcher franchise started out as a series of books written by Polish author Andrzej Sapkowski who first started writing stories about Geralt of Rivia, the famous Witcher, in the mid-1980s. Though the story takes place in a fantasy world, Sapkowksi made it more familiar and relatable by drawing inspiration from European mythology for the monsters Geralt faces. Being Polish, most of the bloodthirsty monsters that populate the Witcher universe comes from Slavic folklore and mythology through both Sapkowski, and the game developers at CD Projekt RED drew from Nordic, Germanic, and Arabic folklore. Folklore within both the games and the books, and more recently the Netflix TV series, is used in a different way than in other games due to the very nature of Slavic folklore. Folktales from the Slavic countries are one of the richest and most diverse mythologies in the world. Traditional Western European fairy tales have become watered down and Disneyfied over countless retellings and interpretations, but Slavic mythology still retains its darker edge which is what makes it perfect for video games.

Polish and Slavic folklore has also become a popular source of inspiration for video games as there is no obvious hero and villain, the characters are all flawed. For example, it could be argued that the immortal crones of Crookback Bog in The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (2015) find their inspiration in the Baba Yaga myth. Baba Yaga is one of the most unique characters from Slavic folklore and is represented as either a capricious crone or one of a trio of sisters who dwells in a hut that stands on chicken legs and is a perfect example of how Slavic folklore isn’t black and white when it comes to who is good and who is evil; in some stories, she is the antagonist while in others she is a source of guidance and helps people on their quests (New World Encyclopedia n.d). The monsters and stories inspired by Slavic Folklore in the Witcher 3 capture the very nature of the original stories, with there being no purely good or bad creatures and the player having the option to spare monsters if they so choose to; with these decisions having an effect on the overall gameplay. An example of this is the quest “Skellige’s Most Wanted” where the player is given the option to try and solve the conflict peacefully by showing that they have helped monsters in the past. This option only shows if the player has previously spared or helped two or more monsters prior to this quest and while it doesn’t prevent a fight from happening it does mean that the player only has to kill one rather than all three of the monsters. The developer’s understanding of the moral complexity of Slavic folklore can be seen here in the way that the player doesn’t have to kill all the monsters, they can try to resolve the encounter peacefully. By allowing the player to choose whether or not to kill certain characters it allows the creatures of folklore to be more than just monsters for the player to kill.

When playing The Witcher 3, I always try to save the creatures if that is an option and from scouring the CD Projekt Red message boards, I am not alone in not wanting to have to always kill the creatures. From a Witcher Forum post titled “What Kind of Witcher are You?” 46 of 51 players said that they would rather save the creature than kill it if that was an option (fig. 1). While this is a small sample size, and relied not only on players choosing to engage with the post but also in a truthful manner, further research into The Witcher message boards shows there is an interest from players for monster games that don’t involve mindless slaughtering as the only or main interaction. While it is nice that the developer does allow some degree of choice when it comes to killing monsters in The Witcher 3, the majority of the time that the creature of Slavic Folklore are used it is as enemies for the player to have to fight as the core fantasy of the game is about becoming Geralt, a Witcher whose job is to kill troublesome monsters.

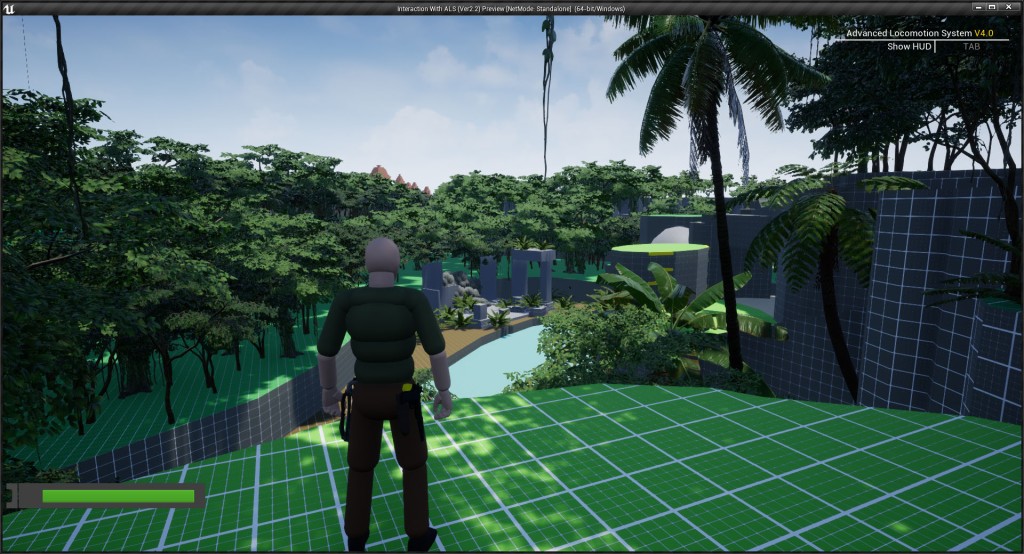

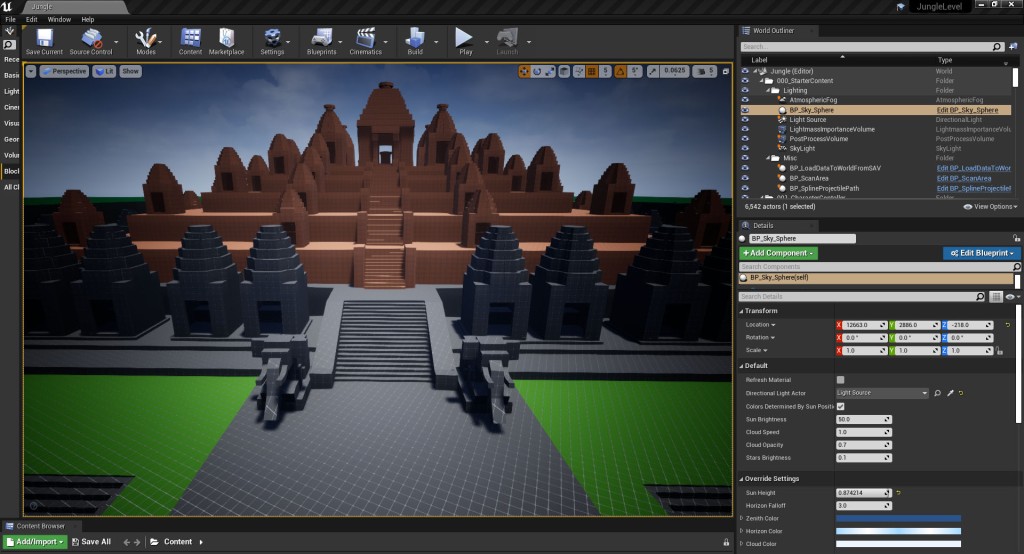

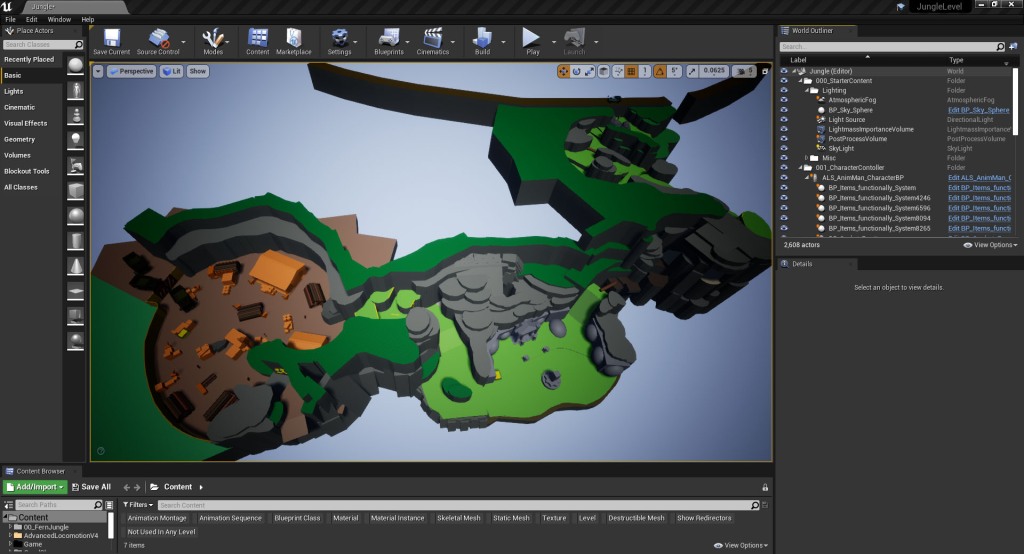

Myths, Legends and folklore as inspiration is not a trend that is going away anytime soon. Project Galileo is an upcoming project by Jyamma Games based upon Italian folklore, while the upcoming FromSoftware release, Elden Ring, is heavily inspired by Lord of the Rings which means at its core it has been inspired by Finnish, Nordic and Icelantic Mythology and Folklore (Shippey 2005). When looking at the way that myth, legends and folklore are used in video games, it is clear that the trend is to use them as inspiration for combat-heavy games, with the creatures found in them often forming the majority of the enemies that the player has to face. For my game, the aim is to utilise these creatures in a different way, to allow the player to interact with these tales in a way other than having to fight or kill them.

“You were right. Monsters are like men. Some’re good, some’re bad, and still others – simply lost…”

Godling – The Witcher 3: The Wild Hunt (2015)

References:

BUCKLEY, Camille. 2017. “How Icelandic Norse Mythology Influenced Tolkien” The Culture Trip [online]. Available at: https://theculturetrip.com/europe/iceland/articles/how-icelandic-norse-mythology-influenced-tolkien/ [accessed 9 February 2022].

CLEASBY; Vigfusson edd. 1974. An Icelandic-English dictionary. Oxford: OUP Oxford

CRAWFORD, Jackson. 2017. Berserkers (Berserkir) and Úlfhéðnar [vidoe clip]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LLDfXpWn3gM [accessed 9 February 2022].

JYAMMA GAMES. n.d. “Explore Italian Folklore” Project Galileo [online]. Available at: https://project-galileo.com/portfolio/discover/explore-italian-folklore-2/ [accessed 9 February 2022].

MACQUEEN, Douglas. 2018. “Wulver: Shetland’s kind and generous werewolf” Transceltic [online]. Available at: https://www.transceltic.com/scottish/wulver-shetlands-kind-and-generous-werewolf [accessed 9 February 2022].

SHIPPEY, Tom. 2005. The Road to Middle-earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology. London: HarperCollins

SIGURDSSON, Gisli. 2020 Interviewed by John Kelly in The Washington Post [online]. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/meet-ratatoskr-mischievous-messenger-squirrel-to-the-viking-gods/2020/04/13/94645e7c-7d95-11ea-a3ee-13e1ae0a3571_story.html [accessed 9 February 2022].

SIMELANE, Smangaliso. 2022. “Elden Ring’s Possible Mythological Inspirations for the Giant Bear Enemy” Gamerant [online]. Available at: https://gamerant.com/elden-ring-mythology-references-giant-bear-enemy/ [accessed 9 February 2022].

THE SCOTSMAN. 2016. “Scottish myths: Wulver the kindhearted Shetland werewolf” The Scotsman [online]. Available at: https://www.scotsman.com/news/people/scottish-myths-wulver-kindhearted-shetland-werewolf-2463904# [accessed 9 February 2022].

UBISOFT NORTH AMERICA. 2021. Assassin’s Creed Valhalla: Wrath of the Druids – Behind the Scenes [vidoe clip]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fNWhtMpcrsQ [accessed 9 February 2022].

Figures:

Figure 1: CD Projek Red Forum, N.D. “What Kind of Witcher Are You?” [Forum Discussion and poll]. Available at: https://forums.cdprojektred.com/index.php?threads/what-kind-of-witcher-are-you.54569/ [accessed 9 February 2022].

Games:

Assassin’s Creed Odyssey. 2018. Ubisoft Montreal, Ubisoft.

Assassin’s Creed: Origins. 2017. Ubisoft Montreal, Ubisoft.

Assassins Creed: Valhalla. 2020. Ubisoft Montreal, Ubisoft.

Assassins Creed: Valhalla DLC Wrath of the Druids. 2021. Ubisoft Montreal, Ubisoft.

Elden Ring. 2022. FromSoftware Inc, Bandai Namco Entertainment.

God of War. 2018. Santa Monica Studio, Sony Interactive Entertainment.

The Witcher. 2007. CD Projekt RED, CD Projekt RED.

The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings. 2011. CD Projekt RED, CD Projekt RED.

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt. 2015. CD Projekt RED, CD Projekt RED.

Films:

The Last Kingdom. 2015 – 2022. [TV Series]. BBC and Netflix.

TV Series:

Vikings. 2013-2020. [TV Series]. History and Amazon Prime Video.

Leave a comment