Inspired by the many different interpretations of the Legends of King Arthur; ‘The Once and Future King” is a grounded fantasy that explores themes of loss, mourning, and hopefulness through a re-imagined, romanticised, and ethereal portrayal of King Arthur’s final resting place on Avalon.

Research

The History of King Arthur

When I started this project, I spent the first few weeks researching the many Legends of King Arthur. The stories of King Arthur as most prominently told through literature; with the literary persona of King Arthur that most people are familiar with beginning with Geoffrey of Monmouth’s pseudo-historical Historia Regum Britanniae, History of the Kings of Britain, written in the 1130s. The textual sources for Arthur are as a result usually divided into those written before Geoffrey’s Historia, pre-Galfridian texts, and those written afterwards, post-Galfridian.

Pre-Galfridian

The earliest literary references to Arthur come from Welsh and Breton sources, which have three key strands:

- Arthur as an unrivalled warrior who functioned as the monster-hunting protector of Britain from all internal and external threats. Some of these are human threats, such as the Saxons he fights in the Historia Brittonum, but the majority are supernatural, including giants, destructive divine boars, dragons, and witches.

- The pre-Galfridian Arthur who was a figure of folklore, particularly topographic or onomastic folklore, and localised magical wonder-tales, the leader of a band of superhuman heroes who live in the wilds of the landscape.

- The third and final strand is that the early Welsh Arthur had a close connection with the Welsh Otherworld, Annwn.

One of the most famous Welsh poetic references to Arthur comes in the collection of heroic death-songs known as Y Gododdin (The Gododdin, attributed to 6th-century poet Aneirin. One stanza praises the bravery of a warrior who slew 300 enemies, but says that despite this, “he was no Arthur” – that is, his feats cannot compare to the valour of Arthur.

In addition to featuring in pre-Galfridian Welsh poems and tales, Arthur appears in other early texts. In particular, Arthur features in a number of well-known lives of post-Roman saints. According to the Life of Saint Gildas, written in the early 12th century by Caradoc of Llancarfan, Arthur is said to have killed Gildas’ brother Hueil and to have rescued his wife Gwenhwyfar from Glastonbury.

Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth’s “Historia Regum Britanniae”, completed c. 1138, contains the first narrative account of Arthur’s life. This work is an imaginative and fanciful account of British kings from the legendary Trojan exile Brutus. Geoffrey places Arthur the same post-Roman period, something he borrowed from pre-Galfridian writings such as the “Annales Cambriae” and “The Historia Brittonum”. He incorporates Arthur’s father Uther Pendragon, his magician advisor Merlin, and the story of Arthur’s Birth. On Uther’s death, the fifteen-year-old Arthur succeeds him as King of Britain and fights a series of battles, culminating in the Battle of Bath.

He then defeats the Picts and Scots before creating an Arthurian empire through his conquests of Ireland, Iceland and the Orkney Islands. After twelve years of peace, Arthur sets out to expand his empire once more, taking control of Norway, Denmark and Gaul which was still held by the Roman Empire when it is conquered. Arthur and his warriors defeat the Roman emperor in Gaul, but as he prepares to march on Rome, Arthur hears that his nephew Mordred, who he had left in charge of Britain, has married his wife and seized the throne. Arthur returns to Britain and defeats and kills Mordred, but he is mortally wounded in the process. He is taken to the isle of Avalon to be healed of his wounds, never to be seen again.

How much of this narrative was Geoffrey’s own invention is open to debate as he borrowed much from earlier texts. However, while names, key events, and titles may have been borrowed; the details of Arthur’s life are his own inventions. His telling of Arthur has enormously influential on the later medieval development of the Arthurian legend. While it was not the only creative force behind Arthurian romance, many of its elements were borrowed and developed forwards such as Merlin and the final fate of Arthur, and it provided the historical framework into which the Romancers’ tales of magical and adventures were inserted.

Post-Galfridian

Romance Traditions

The popularity of Geoffrey’s Historia gave rise to a significant number of new Arthurian works in continental Europe during the 12th and 13th centuries, particularly France. There is clear evidence that Arthur and Arthurian tales were familiar on the Continent before Geoffrey’s work became widely known as “Celtic” names and stories not found within Geoffrey’s “Historia” appear in the Arthurian romances.

From the perspective of Arthur, perhaps the most significant effect of this great outpouring of new Arthurian story was on the role of the king himself: much of this 12th-century and later Arthurian literature centres less on Arthur himself than on characters such as Lancelot and Guinevere, Percival, and Gawain. Whereas Arthur is very much at the centre of the pre-Galfridian material and Geoffrey’s “Historia”, in the romances however he becomes a supporting character. His character also alters significantly. In both the earliest materials and Geoffrey’s text, he is a great and ferocious warrior, in the continental romances however he becomes the “roi fainéant”, the “do-nothing king”. Arthur’s role in these works is frequently that of a wise, dignified, even-tempered, somewhat bland, and occasionally feeble monarch.

Post-Medieval Literature

The end of the Middle Ages brought with it a fall in interest in the stories of King Arthur. Though Malory’s English version of the great French romances was popular, there were increasing attacks upon the truthfulness of the historical framework of the Arthurian romances – established since Geoffrey of Monmouth’s time – and thus the legitimacy of the whole Matter of Britain.

The Matter of Britain is the body of Medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany, and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It was one of the three great story cycles recalled repeatedly in medieval literature, together with the Matter of France, which concerned the legends of Charlemagne, and the Matter of Rome, which included material derived from or inspired by classical mythology.

For example, the 16th-century humanist scholar Polydore Vergil famously rejected the claim that Arthur was the ruler of a post-Roman empire, found throughout the post-Galfridian medieval “chronicle tradition”, to the horror of Welsh and English antiquarians. Social changes associated with the end of the medieval period and the Renaissance also conspired to remove the character of Arthur and his associated legend of some of the power to enthral audiences, with the result that 1634 saw the last printing of Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur for nearly 200 years.

King Arthur and the Arthurian legend were not entirely abandoned, but until the early 19th century the material was taken less seriously and was often used simply as a vehicle for allegories of 17th- and 18th-century politics. The most popular Arthurian tale throughout this period seems to have been that of Tom Thumb, which was told first through chapbooks and later through the political plays of Henry Fielding. Though the action is clearly set in Arthurian Britain, the treatment is humorous, and Arthur appears as a primarily comedic version of his romance character.

The development of the medieval Arthurian cycle and the character of the “Arthur of romance” culminated in “Le Morte d’Arthur”, Thomas Malory’s retelling of the entire legend in a single work in English in the late 15th century. Malory based his book on the various previous romance versions, in particular the Vulgate Cycle, and appears to have aimed at creating a comprehensive and authoritative collection of Arthurian stories. As a result of this, later Arthurian works are often derivative of Malory’s work.

19th Century Revival

In the early 19th century, Medievalism, Romanticism, and the Gothic Revival reawakened the interest in the Legends of King Arthur and the medieval romances. A new code of ethics for 19th-century gentlemen was shaped around the chivalric ideals embodied in the “Arthur of romance”. This renewed interest was most apparent when in 1816, Thomas Malory’s “Le Morte d’Arthur” was reprinted for the first time since 1634.

Initially, the medieval Arthurian legends were of particular interest to poets, inspiring, for example, William Wordsworth to write The Egyptian Maid in 1835, an allegory of the Holy Grail one of Arthur’s most famous quests. Most notably among these was Alfred Tennyson, whose first Arthurian poem “The Lady of Shalott” was published in 1832. Arthur himself played a minor role in some of these works, following in the medieval romance tradition. Tennyson’s Arthurian work reached its peak of popularity with “Idylls of the King”, however, which reworked the entire narrative of Arthur’s life for the Victorian era. It was first published in 1859 and sold over 10,000 copies within the first week. In the “Idyll”, Arthur became a symbol of ideal manhood who ultimately failed, through human weakness, to establish a perfect kingdom on earth.

The interest in the King Arthur of Romance and his associated stories continued through the 19th century and into the 20th, and influenced poets such as William Morris and artists including John Atkinson Grimshaw, Walter Crane and Edward Burne-Jones.

The humorous tale of Tom Thumb, which had been the primary manifestation of Arthur’s legend in the 18th century, was rewritten after the publication of “Idylls”. While Tom maintained his small stature and remained a figure of comic relief, his story now included more elements from the medieval Arthurian romances and Arthur is treated more seriously and historically in these new versions.

The revived Arthurian romance also proved influential in the United States, with such books as Sidney Lanier’s “The Boy’s King Arthur” (1880) reaching wide audiences and providing inspiration for Mark Twain’s satire “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court” (1889). Although the ‘Arthur of romance’ was sometimes central to these new Arthurian works, as he was in Burne-Jones’s painting “The Sleep of Arthur in Avalon” (1881–1898) on other occasions he reverted to his medieval status and is either marginalised or even missing entirely, with Wagner’s Arthurian operas providing a notable instance of the latter, which focus on the Knight Percival and his quest for the Holy Grail.

Furthermore, the revival of interest in Arthur and the Arthurian tales did not continue unabated. By the end of the 19th century, it was confined mainly to Pre-Raphaelite imitators, and it could not avoid being affected by World War I, which damaged the reputation of chivalry and thus interest in its medieval manifestations and Arthur as chivalric role model. The romance tradition did, however, remain sufficiently powerful to persuade Thomas Hardy, Laurence Binyon and John Masefield to compose Arthurian plays, and T. S. Eliot alludes to the Arthur myth, though not Arthur directly, in his poem “The Waste Land”, which mentions the Fisher King.

Tennyson’s works prompted a large number of imitators, generated considerable renewed public interest in the legends of Arthur and the character himself, and in doing so brought Malory’s tales to a wider audience. Indeed, the first modernisation of Malory’s great compilation of Arthur’s tales was published in 1862, shortly after Idylls appeared, and there were six further editions and five competitors before the century ended. The legends of King Arthur had reached the new age and were more popular than ever.

The Modern Legend

In the latter half of the 20th century, the influence of the romance tradition of Arthur continued, through novels such as T. H. White’s “The Once and Future King” (1958), Thomas Berger’s dramatic retelling Arthur Rex (1978) and Marion Zimmer Bradley’s “The Mists of Avalon” (1982) in addition to comic strips such as “Prince Valiant” (1937-onward).

Tennyson had reworked the romance tales of Arthur to suit and comment upon the issues of his day, and the same is often the case with modern treatments too. Bradley’s tale, for example, takes a feminist approach to Arthur and his legend, in contrast to the narratives of Arthur found in medieval materials, and American authors often rework the story of Arthur to be more consistent with values such as equality and democracy. John Cowper Powys’ “Porius: A Romance of the Dark Ages” (1951), takes place in Wales in 499, just prior to the Saxon invasion, where Arthur the Emperor of Britain and is only a supporting character. Instead, Merlin and Nineue, Tennyson’s Vivien or the Lady of the Lake, are major figures. Merlin’s disappearance at the end of the novel keeps with the tradition of magical hibernation, where a king or mage leaves his people for some island or cave to return either at a more propitious or more dangerous time. Powys’ earlier novel, “A Glastonbury Romance” (1932) is concerned with both the Holy Grail and the legend that Arthur is buried at Glastonbury.

The romance version of Arthur has become popular in film and theatre as well. T. H. White’s novel was adapted into the Lerner and Loewe stage musical “Camelot” (1960) and Walt Disney’s animated film “The Sword in the Stone” (1963). Camelot, with its focus on the love of Lancelot and Guinevere and the cuckolding of Arthur, was itself made into a film of the same name in 1967. The romance tradition of Arthur is particularly evident and in critically respected films like Robert Bresson’s “Lancelot du Lac” (1974), Éric Rohmer’s “Perceval le Gallois” (1978) and John “Boorman’s Excalibur” (1981); it is also the main source of the material used in the Arthurian spoof “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” (1975).

Retellings and reimagining’s of the romance tradition are not the only important aspect of the modern legend of King Arthur. Attempts to portray Arthur as a genuine historical figure of c. 500, stripping away the “romance”, have also emerged. As Taylor and Brewer have noted, this return to the medieval “chronicle tradition” of Geoffrey of Monmouth and the Historia Brittonum is a recent trend in Arthurian literature that started in the years following the Second World War, when Arthur’s legendary resistance to Germanic enemies struck a chord in Britain. Clemence Dane’s series of radio plays, The Saviours (1942), used a historical Arthur to embody the spirit of heroic resistance against desperate odds, and Robert Sherriff’s play The Long Sunset (1955) saw Arthur rallying Romano-British resistance against the Germanic invaders. This trend towards placing Arthur in a historical setting is also apparent in historical and fantasy novels published during this period. With attempts to portray Arthur as a genuine historical figure the question on whereabouts he lived was raised. Past stories place him in many different places such as Tintagel Castle to Cornwall and Glastonbury. Historians though favour the home as Arthur being in either Wales, Northern Britain or in more recent years Scotland.

Most recent interpretations of the Legends of Arthur include the BBC’s Merlin series (2008-2012), Guy Ritchie’s King Arthur: Legend of the Sword (2008-2012) and Netflix new series Cursed 2020) based on the book off the same name by Thomas Wheeler published in 2019.

Mind Map

With so many different versions and interpretations of the Legends of Arthur I created a mind map exploring the possible directions I could take with this project. I found it really useful to dump all my thoughts in one place so I can review them all together and begin to work out how they connect.

The main areas that I want to explore as a result of this mind mapping session are the three different versions of King Arthur that visually most interest me:

- The 14th-century version made famous by Sir Thomas Malory and T.H. White

- The historically more likely version of Arthur as a 6th century Romano-British chief

- The recent theory that Arthur was a Scottish chieftain who fought the Romans sometime between the 3rd-9th century

Arthur as a Romano-British Warlord

The historicity of King Arthur has been debated both by academics and popular writers. While there have been many suggestions that the character of Arthur may be based on one or more real historical figures, academic historians today consider King Arthur to be a mythological or folkloric figure.

If Arthur was a real figure then the most likely version is that he was a Romano-British warlord. The first written references to Arthur are written in Welsh, however neither Wales or England existed in the 5th century, so it’s very hard to pin Arthur to a particular national. Arthur is connected to many battles throughout modern-day Wales, England and Scotland, which is why he is often described as a British warrior fighting against the invading Anglo-Saxons. Incidentally, his Saxon enemies would have called him ‘Wealas’ meaning a foreigner – from which we get the word ‘Welsh’.

Scottish Version of Kings Arthur

In the murky history and stories of Avalon, it’s commonly known as the famous island where King Arthur is buried, it’s location on the other hand is one that is heavily debated, speculated, or is otherwise completely a fantasy. There is however one belief as to the location of Avalon that provides a new perspective as to what the Legend of King Arthur was based off of, that Arthur wasn’t the King of the Britons as is commonly known, but was a King in Scotland.

The beliefs I am most interested in is the perhaps many others have in common with Avalon, is the belief that King Arthur was buried on the Scottish isle of Iona, west of the Scottish mainland. Historic the isle of Iona is known as the isle where many Scottish royal families were buried in Post-Roman Scotland, the medieval era in which King Arthur believed to have lived.

T.H. White 14th Century Romantic Version of King Arthur

T.H. White wrote a series of books called the Once and Future King, based upon the 14th century poem Le Morte d’Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory. Though White admits his book’s source material is loosely derived from Le Morte d’Arthur which was originally titled The Whole Book of King Arthur and of His Noble Knights of the Round Table, he reinterprets the epic events, filling them with renewed meaning for a world recovering from World War II.

It is the most popular telling of the legend and the text which Lerner and Loewe adapted into the stage musical Camelot (1960) and Walt Disney’s based their animated film The Sword in the Stone (1963) upon.

Whites novel, “The Once and Future King”, describe Arthur’s tomb in the following way during a conversation between Arthur and Merlin:

“Do you know what is going to be written on your tombstone? Hic jacet Arthurus Rex quondam Rexque futurus. Do you remember your Latin? It means, the once and future king.”

The real-life Avalon: Glastonbury Tor

According to legend, the Glastonbury Tor is The Isle of Avalon, burial site of King Arthur. The Tor seems to have been called Ynys yr Afalon (meaning “The Isle of Avalon”) as it was once surrounded by water, and identified with King Arthur since the alleged discovery of his and Queen Guinevere’s neatly labelled coffins in 1191, recounted by Gerald of Wales. The remains were later moved and lost during the Reformation. Many scholars suspect that this discovery was a pious forgery to substantiate the antiquity of Glastonbury’s foundation and increase its renown. The Isle of Avalon was considered the meeting place of the dead, and the point where they passed to another level of existence. The Holy Grail is also said to be buried beneath Glastonbury Tor, and has also been linked to Chalice Well at the base of the Tor.

The Lore of King Arthur

The Sword in the Stone

The Sword in the Stone is the proof of Arthur’s lineage and right to rule. Robert de Boron’s poem Merlin, the first tale to mention the sword in the stone. The sword in the stone was created to ensure that Arthur, the only son of the last King Uther Pendragon, would ascend to the throne. Arthur was Uther’s illegitimate but only heir; though his existence was kept a secret by both Uther and Merlin to protect him. Months after giving Arthur away, Uther became ill and died. With no known heir to lead the kingdom, the country fell into despair. Rival dukes and lords disputed over who was the best fit to rule England. With no heir to lead the kingdom, the country fell into despair. In the midst of the turmoil, the nobles called on Merlin to find a solution. Having seen to it that baby Arthur was safe, he erected a large stone, on top of which sat an anvil, in a churchyard in Westminster, a region of London. Stuck in the anvil was a sword. An inscription on its blade read:

“Whoso pulleth out this sword from this stone, is rightwise King born of all England.”

The sword was magic, Merlin explained, and only he who was fit to rule England could pull it from the stone. Nobles from far and wide came to try and pull the sword from the stone, but no could accomplish the task. Eventually, the sword became forgotten, and England fell into greater ruin.

Once Arthur had grown up Merlin sort him out, taking on the role of tutor and friend; training Arthur without his knowledge to be the future King of England. One day Merlin takes Arthur before the Sword in the Stone, a crowd had been assembled, and was waiting anxiously to see if anyone could remove the sword. Arthur’s stepbrother, Sir Kay, was the first to try and pull the sword but it would not budge; when Arthur tries however, the sword came loose, and Arthur was crowned King of England.

In Robert de Boron’s version the identity of this sword is revealed to be Excalibur. However, in the most famous English-language version of the Arthurian tales, Malory’s 15th-century “Le Morte d’Arthur”, the sword is known as Caliburn which is broken in combat against King Pellinore.

Excalibur

Excalibur is the King Arthur’s legendary sword; sometimes it is attributed with magical powers or associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain depending on the version of Arthur.

In Arthurian romance, a number of explanations are given for Arthur’s possession of Excalibur. In Robert de Boron’s Merlin Excalibur is the Sword in the Stone and is a symbol of Arthurs right to be King and rule England. However, in the most famous English-language version of the Arthurian tales, Malory’s 15th-century Le Morte d’Arthur, early in his reign Arthur breaks the Sword from the Stone known as Caliburn while in combat against King Pellinore and is given Excalibur by the Lady of the Lake in exchange for a him owing her a favour.

Similarly, in the Post-Vulgate Cycle, Excalibur was given to Arthur by the Lady of the Lake sometime after he began to reign. In the Vulgate Mort Artu, Arthur is at the brink of death and so orders one of his Knights of the Round Table to throw the sword into the enchanted lake; when the knight does and a hand emerges from the lake to catch it. Malory records both the give off Excalibur to Arthur and its returning to the Lady of the Lake in Le Morte d’Arthur.

The Round Table

Accounts differ about the origin of the Round Table, at which Arthur’s knights met to tell of their heroic deeds and adventures; and from which they customarily set off from in search of further quests. The Norman chronicler, Wace, was the first to mention it in his Roman de Brut in 1155. There, he simply says that Arthur devised the idea of a round table to prevent quarrels between his barons over the question of precedence. Layamon then adapted Wace’s account and added to it, describing a quarrel between Arthur’s lords which was settled by a Cornish carpenter who, upon hearing of the problem, created a portable table which could seat 1600 men.

Both Wace and Layamon refer to Breton story-tellers as their source for this idea of a round table. The origins of which may date back to Celtic times, and even to the age of Arthur himself. In the later medieval stories, however, it is Merlin who is responsible for the creation of the table. But it was Malory who upon taking up the theme, developed it and made it into the centrepiece of his epic re-telling.

The Holy Grail

The Holy Grail is a treasure that serves as an important theme in Arthurian literature. Different retellings describe it as a cup, dish or stone with miraculous powers that provide happiness, eternal youth or sustenance in infinite abundance and it is often in the custody of the Fisher King. The term “holy grail” is often used to denote an elusive object or goal that is sought after for its great significance.

The Holy Grail is generally considered to be the cup from which Christ drank at the Last Supper and the one used by Joseph of Arimathea to catch his blood as he hung on the cross. This significance, however, was introduced into the Arthurian legends by Robert de Boron in his verse romance Joseph d’Arimathie, which was probably written in the last decade of the twelfth century or the first couple of years of the thirteenth.

Symbolism in The Once and Future King

When creating my environment, I wanted to pay homage to many different interpretations of the legend that have come before. I wanted to incorporate these versions into my own lore for my interpretation of King Arthur’s final resting place on Avalon.

Arthur has also been used as a model for modern-day behaviour. In the 1930s, the Order of the Fellowship of the Knights of the Round Table was formed in Britain to promote Christian ideals and Arthurian notions of medieval chivalry. The stories of King Arthur and the Christian church are often closely intermingled, with the Holy Grail being an icon representative of both.

Because of this I don’t want the environment to be semantically blunt in the way it approached the themes. I don’t want it to scream ‘this is about King Arthur’ or ‘be mournful, this is a tomb’. It can certainly include those ideas, but I didn’t want it to only be about that or be obviously blunt about them.

I did a lot of research covering Arthurian symbolism and how films and games have used symbolism to convey information to their audiences. From this research I concluded there is nothing worse than having everything spelt out to an audience. A lot of the pleasure that come from watching films and playing games is the fact that the audience gets to work out the story themselves. Because of this I decided to avoid putting Excalibur, the Holy Grail or the Round Table in the scene as they’re all cultural affordance that people recognize instantly and immediately associate with King Arthur.

I wanted the ‘The Once and Future King’ to be a grounded fantasy that conveys the narrative via a breadcrumb trail of mystery and symbolism throughout the environment that clues the players into the story; with these clues being references to previous interpretations of King Arthur. Art director Grant Major best summed up grounded fantasy in the following way:

“Viewers have never been to the place before, but nobody has been surprised with what they see because they imagine that it really could exist. It works because nobody’s shocked with its existence.”

Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Beardsley is the original illustrator of Sir Thomas Malory’s ‘Le Morte d’Arthur’. His work is often the first visual introduction to the Arthurian legends as ‘Le Morte d’Arthur’ is one of the earliest transcriptions of the Arthurian legends. As I wanted to reference the previous interpretations of King Arthur within my environment I decided that I would use Beardsley’s font style for the writing on Arthur’s Tomb.

John Lawrence

John Lawrence illustrated T. H. Whites ‘Once and Future King’ for The Folio Society in 2003. Lawrence used tools and techniques that go back to the 18th century creating illustrations that are contemporary while still fitting with the history of the book. I incorporated the crown symbol from Lawrence’s book cover illustration into the environment as part of the banners that hang around Arthur’s tomb.

Sword in the Stone 1963

Disney’s 1963 film ‘Sword in the Stone’ is based upon T. H. Whites’ first book of the Once and Future King series and is the version of King Arthur that the majority of people are most familiar with. Though the film only shows the journey Arthur took, from the squire Wart to the King of England, it does provide an interesting visual reference to what the world of the Once and Future King could have looked like. As this version is the one most people think of in relation to King Arthur, as many watched it as a child, I wanted to reference it with my environment. As the Sword in the Stone is one of the most famous visuals in regard to the legends of King Arthur, I used the icon scene of Arthur pulling the sword from the stone as a reference for one of the symbols on the banners surround Arthur’s tomb.

Symbols of King Arthur

The legends of Arthur have a rich history of symbols associated with them, especially in regard to Arthur’s Coat of Arms. I wanted to include some of these symbols within the environment. Medieval Kings where traditionally portrayed with shields on their tombs so I wanted to include a coat of arms for the shield that would act as a hint to the audience as to whose tomb this is. The symbols would also be used to decorate the tomb and for the house sigil that decorates the banners surrounding the tomb.

King Arthur already have a couple of House Sigel’s associate him, ever from traditional literature or modern films or TV shows. The most common are:

- Three Or (gold) crowns either on Azure (blue) or Gules (red).

- Thirteen Or (gold) crowns on Azure.

- Argent (white or silver) cross on Vert (green).

- Or (gold), Dragon on Argent (silver) or Gules (red).

These colours and symbols have specific meanings associated with them:

- Or (gold): Signifies wisdom, generosity, glory, constancy and faith.

- Azure (blue): Signifies loyalty, chastity, truth, strength and faith.

- Gules (red): Signifies magnanimity, military strength, warrior and martyr.

- Argent (silver): Signifies truth, sincerity, peace, innocence and purity.

- Vert (green): Signifies abundance, joy, hope and loyalty in love.

- Cross: signifies and represents faith and the Christian church. It is also known as the cross of Christ.

- Crown: Signifies victory, sovereignty and empire. Also called the Celestial crown, they are also sometimes symbols of God.

- Dragon: Signifies power, protectiveness and wealth as they are defenders of treasure.

I decided to go with a different sigil for the shield on the tomb and the banners surrounding the tomb. For the shield I went with the gold dragon. This is a subtle hint to the tomb belonging to King Arthur as it relates back to his surname Pendragon. The gold dragon is also a fitting symbol for King Arthur as the combination of the gold dragon on a shield represents wisdom, power and protectiveness; things that King Arthur is meant to embody.

For the tomb, and the banners that surround it, I decided to go with the House Sigil that is most famously associated with him, the Three Gold Crowns. The three crowns for the banner are on a red background and accompanied by a sword and anvil. While the three gold crowns are a traditional symbol of King Arthur it is not one that is widely recognised unless you have read some of the classic books. The sword in the anvil however is a widely recognised symbol of King Arthur and an important clue as to whose tomb it is.

Avalon and Apple Trees

Avalon, sometimes written Avallon or Avilion, is a legendary island featured in the Arthurian legend. It first appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s 1136 Historia Regum Britanniae as the place where King Arthur’s sword Excalibur was forged and later where Arthur was taken to recover from being gravely wounded at the Battle of Camlann. Since then, the island has become a symbol of Arthurian mythology, alike that of Arthur’s castle Camelot. Avalon is widely associated as the place where King Arthur was taken to his final rest. However, the Welsh, Cornish and Breton tradition believes that Arthur never really died, but would return to lead his people against their enemies.

Avalon can directly be translated to “the isle of fruit, or apple, trees”. In ancient mythology, the Apple is one of the most sacred trees and symbolises good health and future happiness. Since ancient times it has also been known as the ‘Tree of Love’ and is associated with Aphrodites, goddess of love. Celtic mythology often mentions apples as the fruit of the gods that brings a sense of wholeness, healing and connection with nature; and in Victorian flower language Apple Blossom means better things to come, peace and hope.

Apples are a common feature in Arthurian legends, and can be traced back to as early as c.1150 in Geoffrey of Monmouth work. As I want the scene to have an underlying feeling of hopefulness the apple tree in blossom is a perfect symbol to include in the scene; as well as acting as another key reference and clue to King Arthur.

Knights of the Round Table

While I didn’t want to include a visual representation of the round table it’s self I did want to include the Knights. Different stories have different numbers of knights, ranging from 12 to more than 150, but the most commonly reference number is 12. As a result, I choose to have 12 statues to Knights lining the path down to and surrounding Arthur’s tomb, protecting Arthur is death as they did in life.

As Arthur’s protectors the knights, all except one, hold a sword and stoically stand guard over Arthur’s eternal resting place. Arthur was betrayed and killed by Mordred, who had been one of his twelve knights. The fallen sword, lying face down on the floor, is a subtle hint to Mordred’s betrayal.

In a node to another version of King Arthur the quote on the sword, “In serving each other we become free” is from the film The First Knight (1995). The films plot focus on the betrayal of one of Arthur’s knights and the battle that ensues as a result so was a fitting film to reference on the Knights swords. The quote also sums up the oath taken by the Knights of the round table to serve their kingdom and each other.

‘Sic Parvis Magma’

“SIC PARVIS MAGMA”, meaning “Greatness from Small Beginnings”, is not just a nod to one of my favourite games franchise, the Uncharted series, but also perfectly sums up Arthurs journey. Arthur starts life out, not as a prince, but as a squire; unaware of what the future has instore for him. At this point in his life Arthur is nobody, he’s not as a King, but as Wart – a lowly squire with a gloomy future ahead of him. In the end though Arthur becomes a great King who unites the kingdoms and formed the Knights of the Round Table.

Celtic Knots

Celtic mythology and King Arthur have always gone hand in hand, with Merlin the Wizard often being considered a Celtic Druid and the Isle of Avalon being of the legendary island of Celtic origins. With Avalon being so closely linked with Celtic mythology it felt important to include Celtic symbolism within the environment of the Once and Future King. As such, “The Once and Future King” features multiple Celtic Symbols within the environment such as on Arthur’s tomb, the Mausoleum, and the Knight Statues. I decided to use a mixture of existing Celtic knots as well as creating my own, by combining existing ones, to create knots with specific meanings. Each knot has its own specific meaning:

The Triquetra / Trinity Knot – The Power of Three

There is no single Celtic symbol for family, but there are several ancient Celtic knots that represent the meanings of eternal love, strength, and family unity. The Triquetra, also known as the Trinity Knot or Celtic Triangle, is thought to be the oldest symbol of spirituality. It is depicted in the 9th century Book of Kells and also appears in Norwegian stave churches from the 11th century.

The Triquetra, with no beginning and no end, represents unity and eternal spiritual life. The symbols line interweaves through the circle in an unbroken flow. Many believe that this symbol represents the pillars of early Celtic Christian teachings of the Holy Trinity, God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. When enclosed in a circle it also represents the unity of spirit. The circle protects it, so the symbolic spirit cannot be broken.

The Triskelion – A Symbol of Eternal Life

The Triskelion, also known as the Triskele, is another of the ancient Irish Celtic symbols thought to have been around during Neolithic times, around 3,200 years BC. The Celtic spiral is one of the oldest and most primitive decorations on earth and is believed to represent the sun or ethereal radiation energy.

This spiral symbol reflects the Celtic belief that everything important comes in threes. The Triskelion has three clockwise spirals connecting from a central hub. Also called the triple spiral, the Triskelion has rotational symmetry and is very common in Celtic art and architecture.

Celtic spirals that are clockwise are believed to have a meaning connected to harmony or earth; if they are anti-clockwise they are thought to be pagan symbols that manipulate nature. The meaning of the Celtic Triskelion is seen as a symbol of strength and progress. As it appears to be moving, the Triskelion also represents the will to move forward and overcome adversity.

Serch Bythol – Family and Loyalty

Although less well known than some other Celtic symbols, the Serch Bythol is important, as it shows the early Celts were deeply in touch with their emotions and relationships. The Serch Bythol symbol is made from two Celtic knots/triskeles to symbolize the everlasting love between two people, whether that be romantic or platonic. The two defined yet closely intertwined parts represent two people joined together forever in body, mind, and spirit.

The unification of the symmetrical left and right halves signify the bringing together of body, mind and spirit with the central circle representing the unbreakable love that binds them together.

Shield Knot – Protection from Negativity

Shield Knot is one of the oldest but lesser-known but equally recognisable Celtic symbols. The shield knot was traditionally a symbol of protection, to ward off evil spirits and harm from both the home and the battlefield. Many soldiers would carry amulets of the charm with them when going to the battlefield. Alternatively, this symbol was placed on the battlefield to protect the soldiers from harm.

However, the shield knot can also be interpreted to represent eternal love, unity, and loyalty between friends and family. It’s endless loop, with no end or beginning, represents everlasting love while the knot image represents an unbreakable bond.

Sailor’s Knot – the Strength of Friendship

The Sailor’s knot is a simple but popular design features two intertwined ropes. It is thought that this design was initially created by sailors during extended voyages at sea, to keep loved ones in their thoughts. As such, this knot is also seen as a symbol of friendship, loyalty, and love. Though simple to tie, the sailor’s knot is one of the strongest knots, symbolizing a bond that grows stronger under pressure and with the passage of time. While mainly representative of eternal friendship, harmony, affection, and love, but are also believed to bring good fortune to the wearer and to keep them safe at sea.

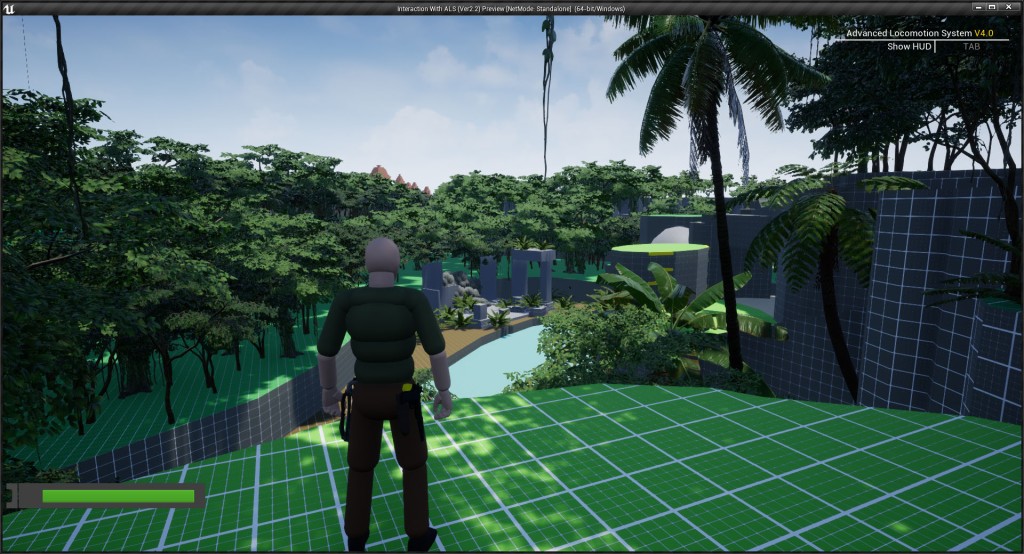

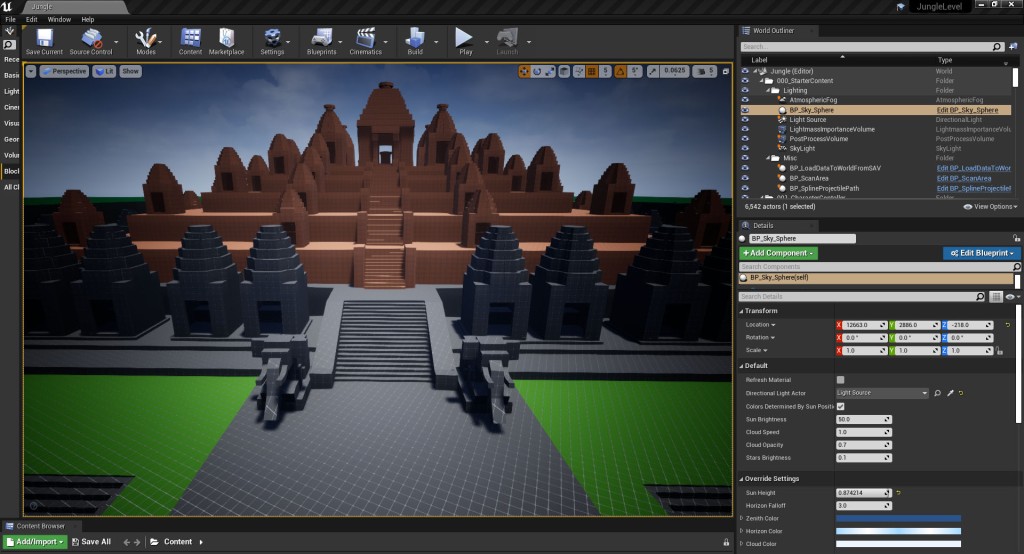

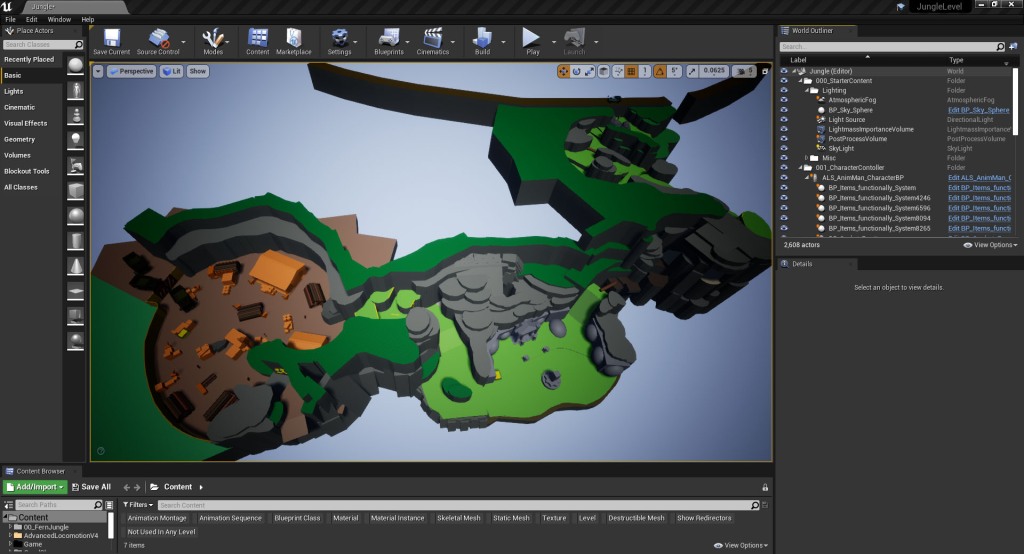

The project covers many areas within the gaming pipeline including modelling, sculpting, texturing, environment design, look development, and cinematography.

This short environment cinematic was made using custom assets created specifically for ‘The Once and Future King’ along with additional assets courtesy of the Unreal Engine Marketplace and Megascans.

The music is “Verses” By Ólafur Arnalds, Alice Sara Ott

Leave a comment